December 2020 marked 50 years since the release of the film “Love Story” in December 1970. This film played a role in the burgeoning romance between me and the astonishing man who became my husband a few months later. I’ll call him Marv.

ANOTHER LOVE STORY

We waited in a long line outside the theater in chilly Westwood. The air was nothing like the frigid nighttime air that would have enveloped us in Chicago or Boston. But we were in LA, and for LA it was a chilly December night.

We didn’t mind waiting. We were too enthralled with each other, with Westwood, and with the prospect of seeing “Love Story” on the big screen.

I’d met Marv two months earlier at a reception on the UCLA campus. I’d moved from Chicago to take a job at UCLA and was eager to meet new people. The reception was taking place on a Sunday afternoon in October, and I decided to show up.

I didn’t know anyone there—I’d been in LA for only six weeks. I wandered over to the “cookie table” and was pondering which cookies to sample when a woman approached me. “Are you by yourself because you want to be, or would you like to meet some other people?” she asked.

I immediately responded that I’d like to meet other people, and she led me to a group of four men. She began by introducing her husband, a bearded middle-aged math professor, who was accompanied by three much younger men. As I glanced at the younger men, I instantly recognized one of them–a good-looking guy I’d seen around my apartment building near the campus.

The professor explained that these young men were there because they were new math faculty, and he asked me why I was there. I told him I was working at the law school. He then asked where I’d gone to law school. When I said Harvard, he turned to the good-looking guy and said, “Marv went to Harvard, too.”

Thus began my bond with Marv. We had Harvard in common.

It turned out that Marv was at UCLA for a special one-year program in the math department. When we began talking at the reception, Marv discovered what I already knew—we lived in the same apartment building. Did I give him my phone number? I must have because a day or two later he called and asked me to go to dinner.

We agreed that I would meet him at his apartment and make our dinner plans there. So on Saturday night I walked a short distance from my apartment to his apartment on the same floor.

Marv and I had both searched for a studio apartment in Westwood at the same time. At the end of my search, I decided that I preferred a building on Kelton. Hoping to rent a relatively inexpensive studio there, I returned and learned that the last studio had just been rented. It turned out that the renter was Marv.

So, because someone (namely Marv) had just rented the last available studio in that building, I had to decide whether to rent a one-bedroom I could barely afford. It was a stretch for me, financially. But I decided to go ahead and rent it.

Destiny?

When he answered his door, Marv welcomed me and handed me a copy of a paperback book, “101 Nights in California.” We sat together on his sofa, looking through the book’s list of restaurants, along with their menus. “You pick wherever you want to go,” he said.

My jaw nearly dropped. It was 1970, and it was almost unimaginable that a man would say that to a brand new date, allowing her to choose the restaurant where they’d dine that night. I knew immediately that Marv just might be the right man for me. He was certainly unlike anyone I’d ever dated before.

I’d already dated some pretty good guys. But when men met me during my years at law school, or later learned that I was a lawyer, only the few who were immensely secure chose to date me. Others fell by the wayside.

Marv was completely secure and non-threatened by someone like me. He actually relished having a smart woman in his life. And that never changed.

That evening, I chose a French restaurant in Santa Monica called Le Cellier. How was our dinner there? In short, it was magical. We not only had a splendid French meal, but we also used our time together to learn a lot about each other. My hunch that Marv was possibly the perfect man for me was proving to be correct.

We proceeded to have one promising date after another. Dinner at a small Italian restaurant in Westwood. A Halloween party in Pacific Palisades. Viewing the startling film “Joe,” starring Peter Boyle. (We later ran into Boyle when we ate at a health-food restaurant in LA.)

By December we were hovering on the precipice of falling in love. We’d heard the buzz about “Love Story,” and both of us were eager to see it. So there we were, waiting in a long line of moviegoers at the Westwood Village Theater that chilly night.

The plot of “Love Story” wasn’t totally unknown to me. I’d already read Erich Segal’s story shortly before I’d moved to LA. It grabbed me right away. It was set, after all, in Cambridge, and its leading characters were students at Harvard. I’d spent three years there getting my law degree just a few years earlier.

The story was sappy and had a terribly sad ending. But I relished the Harvard setting, and I couldn’t wait to see the film based on it. When Marv learned a little bit about it, he wanted to see it too. He’d finished college at Harvard just before I arrived at the law school

We soon found ourselves inside the theater, every seat filled with excited patrons like us, and began watching Hollywood’s “Love Story,” our eyes glued to the screen.

What did we think of the movie that night? I truthfully don’t remember, and Marv is no longer here to recall it with me. So I recently decided to re-watch the film—twice–to reflect on it and what it may have meant to us at the time.

In 1970, enamored with my companion, I most likely loved the film and its countless depictions of student life at Harvard. Both Marv and I had attended Harvard at almost the same time as author Erich Segal.

The two lead actors, Ryan O’Neal (playing Oliver) and Ali MacGraw (playing Jenny), were also contemporaries who could have been Harvard students when we were. Let’s add Tommy Lee Jones, whose first film role is one of Oliver’s roommates. He was himself a Harvard grad, class of ‘69. (Segal reportedly based Oliver on two of his friends: Harvard roommates Tommy Lee Jones and Al Gore.) By the way, Tommy’s name in the credits is Tom Lee Jones.

Marv and I certainly relished the scenes set in a variety of Harvard locations, including the hockey arena where Oliver stars on the school’s hockey team and where I had skated (badly) with a date from the business school. In another scene, the two leads ecstatically make snow-angels on the snow-covered campus.

And I loved watching Oliver searching for Jenny in the Music Building, a building located very close to the law school, where I occasionally escaped from my studies by listening to old 78 LP records in a soundproof booth.

Overall, Marv and I probably found most of the film a lightweight take on life as a Harvard student (although darker days followed as the story moved toward its tragic end). I’m sure we were also moved by the haunting music composed by Francis Lai, an unquestionably brilliant addition to the film that earned its only Oscar (out of seven nominations).

Seeing “Love Story” together that chilly night must have been wonderful.

But watching the film again, 50 years later? I have to be honest: I found it terribly disappointing.

The film was an enormous hit at the box office, earning $130 million—the equivalent of $1 billion today.

It was a box-office phenomenon, a tearjerker that offered its audience a classic love story filled with amorous scenes and, ultimately, tragedy.

But….

Fifty years later, I found the two leads far less appealing than I remembered.

Ryan O’Neal, who plays highly-privileged Oliver Barrett IV, and Ali MacGraw, who plays Jenny, a super-smart girl from the wrong side of the tracks, encounter each other on the Harvard campus as undergrads. After some sparring, they quickly fall into each other’s arms. But I didn’t find either them or their relationship overwhelmingly endearing.

Ali MacGraw’s character, Jenny, strikes me now as borderline obnoxious. She’s constantly smirking, overly impressed with her brain-power and witty repartee.

Even Oliver, who falls madly in love with her, calls her “the supreme Radcliffe smart-ass” and a “conceited Radcliffe bitch.” (As you probably know, Radcliffe was the women’s college affiliated with Harvard before Harvard College itself admitted women.)

Jenny would repeatedly retaliate, ridiculing Oliver by calling him “preppie,” a term used at the time by non-privileged students in an attempt to diminish the puffed-up opinion that privileged prep-school graduates had of themselves.

Jenny may have been Hollywood’s version of a sharp young college woman of her time, but 50 years later, I view her character as unrelatable and hard to take.

I received my own degrees at a rigorous college, a demanding grad school, and a world-renowned law school. My classmates included some of the smartest women I’ve ever known. But I don’t recall ever encountering any bright young women who exemplified the kind of “smart-ass” behavior Jenny displays. If they existed, they clearly stayed out of my world.

The film has other flaws. In one scene, filmed near a doorway to Langdell Hall (the still-imposing law school building that houses its vast law library), Jenny bicycles to where Oliver is perched and proceeds to make him a peanut butter sandwich while he is so engrossed in a book that he barely notices her presence. This scene is ludicrous. Law students are traditionally super-focused on their studies. Well, at least some of them are. But Oliver’s ignoring a beloved spouse who’s gone out of her way to please him in this way is offensive and totally contrary to the “loving” tone in the rest of the film. In short, ludicrous.

The movie also became famous for its often quoted line, “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” The absurdity of that line struck me back in 1970 and has stayed with me ever since. I’ve never understood why it garnered so much attention. Don’t we all say “I’m sorry” when we’ve done something hurtful? Especially to someone we love?

Interviewed by Ben Mankiewicz in March 2021 (on CBS Sunday Morning), both Ali MacGraw and Ryan O’Neal (still vibrant and still in touch with each other) confessed that they never understood the line either. “What does it mean?” Mankiewicz asked. MacGraw’s response: “I don’t know.”

One more thing about that famous line: If you watch the hilarious 1972 screwball comedy “What’s Up, Doc?” you’ll probably get a kick out of a scene at the very end. Barbra Streisand cleverly mocks the “Love means never…” line while traveling on a plane with her co-star (and “Love Story” lead) Ryan O’Neal.

Another line in the film, this one spoken by Oliver’s father, struck me as remarkable as I listened to it 50 years after the film first appeared. When his father, played by veteran actor Ray Milland, learns that Oliver has been admitted to Harvard Law School, he tells Oliver that he’ll probably be “the first Barrett on the Supreme Court.” Just think about this line. Who could have predicted in 1970 that a judge named Barrett would actually be appointed to the Supreme Court in 2020?

One more thing about Jenny: Yes, women used to give up great opportunities in order to marry Mr. Right, and many probably still do. But I was heartily disappointed that Jenny so casually gave up a scholarship to study music in Paris with Nadia Boulanger so she could stay in Cambridge while Oliver finished his law degree.

What’s worse, instead of insisting that she seize that opportunity, Oliver selfishly thought of himself first, begging her not to leave him. Jenny winds up teaching at a children’s school instead of pursuing her undeniable musical talent.

I like to think that today (at least before the pandemic changed things) a smart young Jenny would tell Oliver, “I’m sorry, darling, but I really don’t want to give up this fabulous opportunity. Why don’t you meet me in Paris? Or wait for me here in Cambridge for a year or two? We can then pick up where we left off.”

But I’m probably being unfair to most of the young women of that era. I’m certainly aware that the prevailing culture in 1970 did not encourage that sort of decision.

When I decided to marry Marv in 1971 and leave my job at UCLA to move with him to Ann Arbor, Michigan, I wasn’t giving up anything like Paris and Nadia Boulanger. For one thing, I had had a perilous experience in LA with a major earthquake and its aftershocks. I was also aware of other negative features of life in LA.

And shortly after Marv asked me to marry him, we set off on an eight-day road trip from LA to San Francisco via Route 1, along the spectacular California coast. Spending every minute of those eight days together convinced me that Marv and I were truly meant to be together.

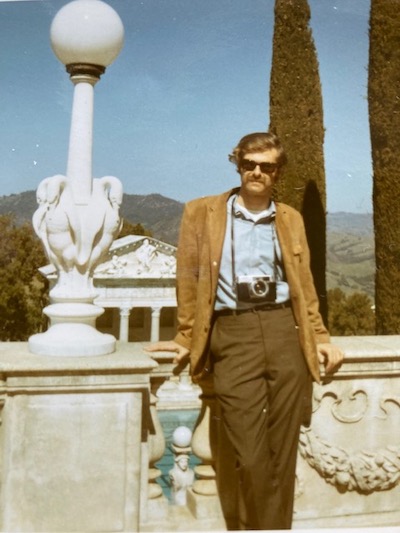

(By the way, during our trip we visited the gorgeous Hearst Mansion –now called the Hearst Castle–in San Simeon, which Orson Welles used as his model for Xanadu in “Citizen Kane.”)

Touring Hearst Castle 1971, Photos: Courtesy of Susan Alexander

So I decided, on balance, that moving with Marv to Ann Arbor would mean moving to a tranquil, leafy-green, and non-shaky place where I could live with the man I adored. The man who clearly adored me, too.

I was certain that I would find interesting and meaningful work to do, and I did.

Both of us hoped to return to California after a few years in Ann Arbor, where Marv was on the University of Michigan math faculty. But when that didn’t work out, and we jointly decided to leave Ann Arbor, we settled elsewhere—happily–because it meant that we could stay together.

I’ve made many unwise choices during my life. The list is a long one. But choosing to marry Marv, leave LA, and live with him for the rest of our gloriously happy married life was not one of them.

The unwise choices were my own, and loving Marv was never the reason why I made any of them.

On the contrary, life with Marv was in many ways the magical life I envisioned when we shared dinner for the first time at Le Cellier in Santa Monica in October 1970.

It was, in the end, and forever, another love story.

Photos are courtesy of Susan Alexander unless otherwise noted.

Be the first to comment